So, you're playing a CTF and you decide to try the pwn category for the first time. You're given a file with a weird or no extension, and a string that looks something like nc mydoma.in 12345. You figure out what NetCat is and you connect to the server, which asks you for some input and kicks you out no matter what you enter. You've never seen a challenge like this before.

Allow me to introduce you to the Buffer Overflow vulnerability. This is one of the most well known and commonly exploited vulnerabilities in the world, or at the very least, used to be. Ever since the famous paper was released, Smashing The Stack For Fun And Profit, no C program has been safe. This vulnerability allows an attacker to functionally run whatever code they want on a running C program that accepts user input, and doesn't properly limit the length of that input.

There have been many summaries and writeups of this kind of problem, as well as variations of it, online. I'll give a special shoutout to Rapid7's explanation, as they go into the practical nature of this vulnerability and cover many of the same things this blog post touches on as well. For right now, I want to return to the original question. Say you're playing a CTF and you come across a challenge that requires you to exploit this vulnerability. How do you do it right?

Let's get right into it. These challenges will typically give you two things. The first is an executable binary file compiled from the C programming language. This is the file with the weird extension you may have encountered. This file can be run in a standard Linux command line (or a Mac terminal, or in WSL for Windows). Simply make it executable and run it with the following commands:

chmod +x challenge-file-name && ./challenge-file-name

Once you run it, you should see some output in the terminal that looks strangely similar. Now look at the second thing the challenge gives you: a connection string. This string gives you all the information you need to connect to a remote server on the internet. Most commonly, this is a NetCat command that looks something like this:

nc <ip address or domain> <port number> e.g. nc 12.34.567.89 1234

Go ahead and type this string into your terminal and run it. Notice how it gives the exact same output as when you ran the executable binary? That's because it's the exact same program. Your goal for this challenge is to connect to this remote server and exploit the program running on it, and you're given this exact program so you can analyze the code and test your exploit.

So now that we know exactly what we're being given, it's time to analyze the executable binary. What's actually being run on this server?

There are many binary analysis tools out there you can use. In this tutorial we will use the Gnu Debugger, or gdb. This is a command line tool that comes pre-installed on most Linux distributions, and there's even an online version! (though you do need the source code for this version)

To start analyzing the challenge binary, run the following commmand:

gdb challenge-file-name

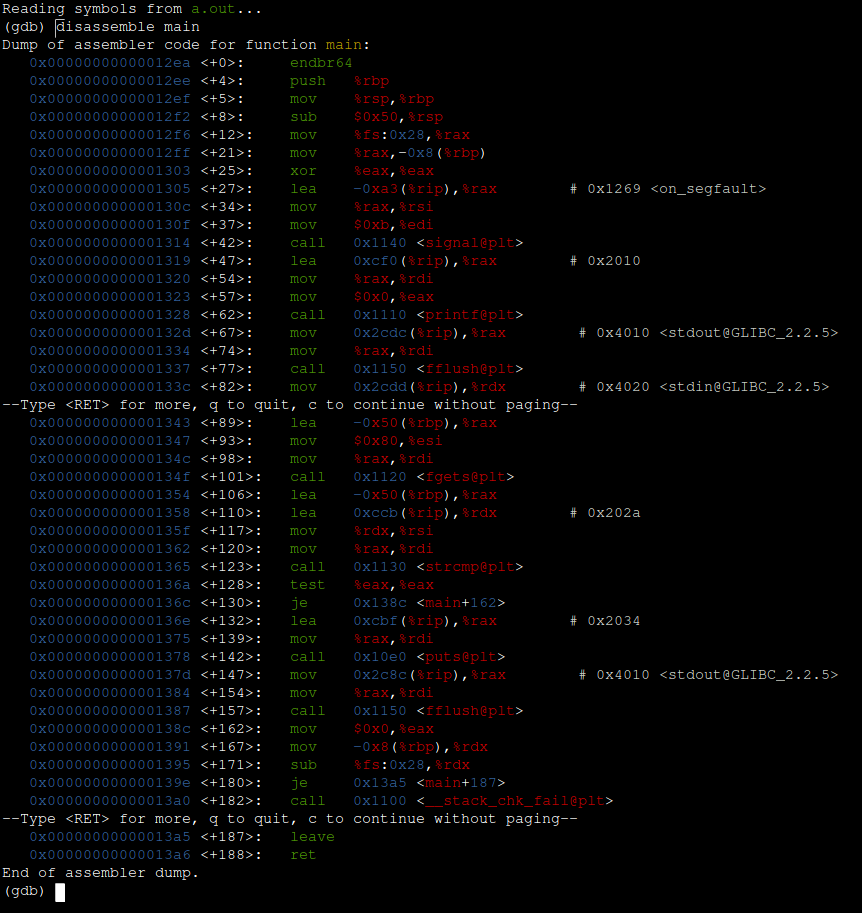

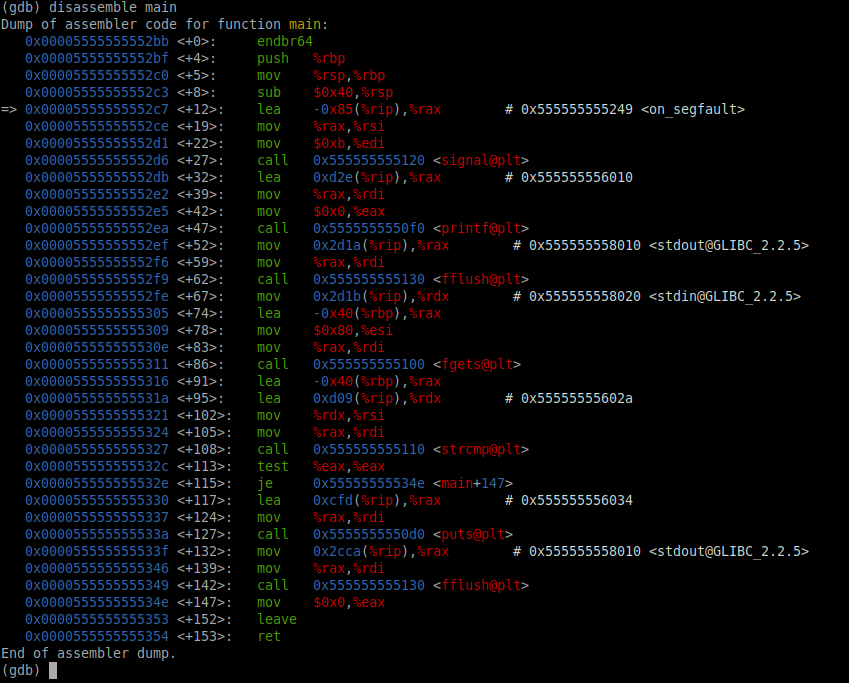

So, we know that this program accepts some form of input from a user, but that doesn't necessarily mean that it has a buffer overflow vulnerability. Let's take a look at the code itself to confirm for sure that it is vulnerable. Unfortunately, we aren't given the exact C source code for this program, but we can look at something similar and more lower-level. It's called x86 Assembly Language:

Assembly languages of all kinds are very complicated to understand and analyze, it's fine if you don't understand anything you see in the picture above. While I do recommend studying up on what assembly language is and how it works, that wont be necessary for this guide. For now, just understand that this is the representation of the program that your computer actually sees and understands, and knows how to execute. And it can be analyzed just like any other language.

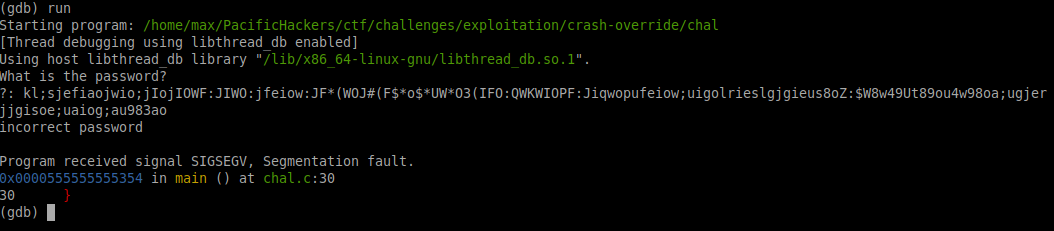

Going back to the picture above, we are specifically looking at the assembly code for the "main" function. On some of the lines, in red text and enclosed in angle brackets <>, are function names like "printf@plt", "fgets@plt" and "strcmp@plt". These are standard C library functions. "fgets" in particular is a function that accepts input, and can potentially be vulnerable to buffer overflow. Let's try it out! To run the program, enter the run command in gdb, and when it asks for your input, put in like 100 random characters.

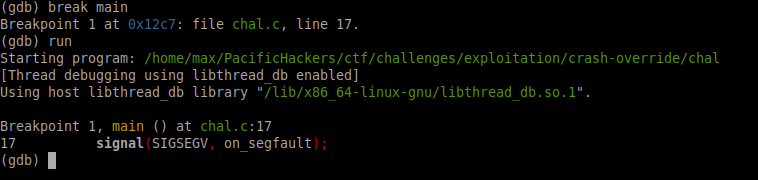

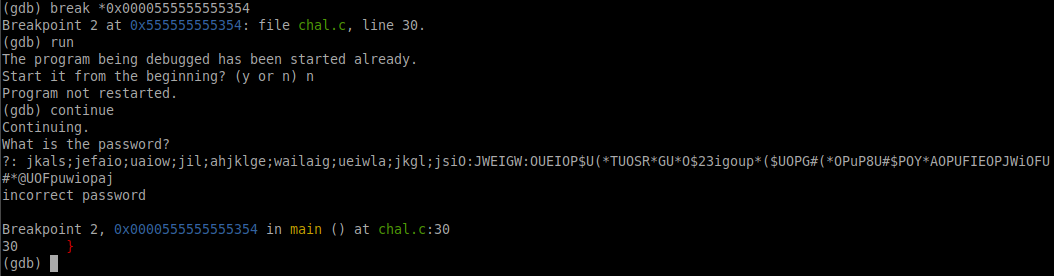

Bingo! Our input caused a Segmentation Fault! If the program handled our input correctly it would have just output "incorrect password", but instead something inside broke! Let's take a look at what exactly broke. Run the program again, but before you do, run the command break main to make the program stop right before the "main" function.

This is where we have to talk about something called Address Space Layout Randomization. You need to understand computer architecture to fully get it, but basically it means that each time you run a program, it is loaded into a random memory space on your computer. We want to look at the program at the exact point in time that we broke it with our input, so we need to have the exact memory address of that point in the code. Go ahead and run disassemble main again and see how the numbers on the left side change.

Now they all have a bunch of 5s! Your numbers are going to be different from mine since they are random memory addresses. This shouldn't matter though, all you have to do now is set a breakpoint at the very last "ret" instruction in the code. Run break *0x0000555555555354, replacing my memory address with the one showing up on the very last line of your assembly code. Then run continue and send it your spaghetti.

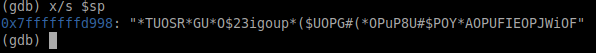

Perfect, we've hit the breakpoint. Now run x/s $sp - e(x)amine (s)tring at (s)tack (p)ointer.

There it is! All that spaghetti we inputted. Basically, when we sent a super long string to the program input, it put the first part of it into a variable, but didn't have anywhere to put the rest of it, so it "overflowed" into the program stack!

I'll leave you at this for now. So far, we've confirmed that this program has a buffer overflow vulnerability, have successfully crashed the program, and can see exactly where our overflowed input is being stored. In the next post, I'll touch on how exactly to get that "code execution" promised in the title of this post, so you can actually solve this CTF challenge. Hope this was helpful, and I'll see you in the next one!